Zen painting: Zen Buddhism and artistic exchange

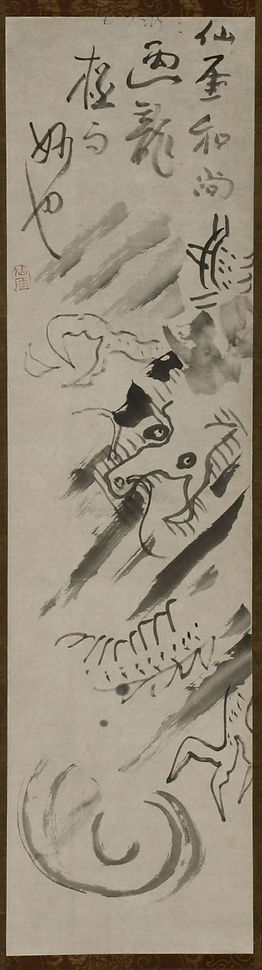

Attributed to Sengai (1750-1837)

Dragon

n.d.

Sumi ink drawing in scroll format

67 x 12 in.

Museum purchase

This painting of dragon bears the signature and seal by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) from the Edo period (1603-1868). The exact date that this work of art was created is unknown. It was purchased by the museum in May of 1973. This scroll was made with sumi ink and stands for the uninhibited and playful style Sengai is known for. The brushstrokes seem quick and rushed without creating much depth to the drawing, along with a cursive style to the calligraphic inscriptions. This “rushed” brushstroke style shows Sengai’s playfulness that he conveys in his art. He expresses this informality throughout his art to reflect a free attitude unbound by conventions which originates from Zen Buddhism.[1]

The dragon in Japan has complicated symbolism, combining myths and lore from China, India, and Japan. Most of all, it is associated with water and rain, seen here in the mists and clouds surrounding the dragon.[2] Sengai used a lot of negative space to bring attention to the dragon. The shapes, shading, and lines in this scroll are much more defined when your eyes draw closer to the dragon’s face. Sengai is making these aspects more defined when you look closer to the dragon, as he is trying to direct the viewer’s attention to the dragon.

Towards the top of the scroll, there is an inscription. The inscription says, “Monk Sengai paints dragon, it is magnificent.” This is an overly simplistic text compared to Sengai’s typical inscriptions that reflect his musing and ideas as a Zen monk. Sengai spent his whole life as a Zen monk who always tried to promote peace and happiness of earth through not only his whimsical and humorous art but his teachings as well. After serving two decades as an abbot, he devoted his life to his art. He would teach calligraphy and painting, where his teachings would reflect his beliefs of peace and happiness.[3]

In “Dragon,” Sengai combines Zen art with his values through his playful and whimsical brushstrokes. The dragon, being a sign of good fortune and power, further explains his beliefs in peace and spiritual freedom. This scroll captures Edo-period Japanese Zen art (Zenga) in its playful art style, which made Zenga popular in Japan and globally in the post-war era. Zenga has its origins in Zen art in medieval Japan when Zen (or Chan in Chinese) Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China.[4] Sengai’s scroll proves the close ties between Japan and China in art and religion.

Deston Gornick

[1] Galit Aviman, “On monkeys, illusion and the moon in the paintings of Hakuin Ekaku and Sengai Gibon,” Japan Studies Association Journal Vol. 8 (2010): 209.[2] Zoey Kolligian, “The Japanese Dragon in Art and Mythology,” Asian Art and Architecture, Connecticut College, December 17, 2023, https://diluo.digital.conncoll.edu/Asianart/author/zkolligiaconncoll-edu/

[3] Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Sengai: The Zen of Ink and Paper (Greenwic, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1971.

[4] Yukio Lippit, “Zenga: A Brief History,” None Whatsoever: Zenga Paintings from the Gitter-Yelen Collection, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2023, https://emuseum.mfah.org/catalogues/gitter-yelen-collection/menu/zenga-a-brief-history

Chinese Influence in Japan Zen Painting

Zen painting is a famous genre of painting from the Edo period in Japan. Zen paintings—works of art created by Buddhist monks — have close ties to Zen Buddhism. Zen monks spread the teachings and ideas of Zen Buddhism in their works, all in the hope of awakening people's inner worlds and minds, as well as contributing to their own personal cultivation through their paintings.[1] Japanese Zen paintings, with their simple brushstrokes and spiritual connotations, have become a representative category of art that is deeply influenced by Chinese Chan (Zen in Japanese) culture.

Chan/Zen Buddhism, originating in India, spread into China and became popular during the Northern and Southern Dynasties period. The influence of Buddhism led to the creation of different forms of Chinese art, each with religious aspects.[2] Chan Buddhist art began to develop as early as the Tang Dynasty in China, and Buddhism’s influence on the art form reached its peak during the Song Dynasty. It was also during this period that monochrome ink painting became the main form of expression for Chan Buddhist paintings. Chan paintings were simple and straightforward, emphasizing simplicity and valuing brushwork that could convey the artist's inner spirit while spreading the teachings of Buddhism. Monochromatic ink painting served as a medium to spread the philosophy and connected the paintings to the spiritual world of man by capturing momentary thought.[3] For these Chan paintings, artists usually choose natural landscapes or objects as their subject matter, including mountains, flowers, birds, and bamboo. These elements have different symbolic meanings in China, and artists prefer to depict these subjects as a reflection of a person's inner spirit and as a teaching of what they should become.[4]

During the Song dynasty, many Japanese monks and artists began to visit and study in China. During this time, called the Kamakura period in Japan, the Chinese style of Buddhist painting was established in Japan as Zen painting.[5] In addition to art, Chinese calligraphy, literature, and philosophical ideas were also brought to Japan.[6] The samurai class – the warrior class in Japan — found Chan Buddhism’s simple and rigorous philosophical ideas appealing. As a result, Zen Buddhism was widely accepted and integrated into Japanese culture. This led to the widespread acceptance and integration of Zen into Japanese culture.[7]

The minimalist monochromatic ink paintings imported from China had a profound impact on Japanese painting and art forms,[8] and monochromatic ink paintings have since become an iconic form of Zen art in Japan, forming the primary medium of Zen art. Chinese artists pioneered this technique of relying on ink shades to create mood and texture, which was adopted by Japanese artists as a minimalist tool for conveying Zen ideas. The directness of the brushstrokes and the capture of instantaneous thoughts in Chinese Buddhist art caught the interest of Japanese Zen artists. This idea of simplicity, transience, and spontaneity became the indispensable spirit behind Japanese Zen painting. In fact, “simplicity” and “rusticity” took their place in the aesthetic of Japanese art and came to be known as Wabi-sabi, an aesthetic of natural simplicity brought about by the spirit of Zen.[9]

In addition to style and inner spirit, the subject matter of Japanese Zen paintings also draws heavily on the traditions of Chinese Chan art. Natural themes such as landscapes, flowers, birds, animals and figures, which were popular in Chan paintings, were also favored by Japanese monks and artists, and symbolized a spiritual uniting of man and nature. Animals were an especially popular element, as viewers can see from Sengai’s work.

From the introduction of Zen Buddhism to the influence brought by Chinese ink painting, China laid the foundation for the development of Japanese Zen art.[10] Rather than simply copying the forms of Chinese Chan art exactly, Japanese artists have adapted them, incorporating local culture, context and aesthetics into their paintings to create a unique artistic tradition that continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the world.[11] By combining Chinese artistic practice with Japanese innovation, Zen painting has become a powerful medium of spiritual expression, embodying its pursuit of Zen cultural practice and its sense of personal enlightenment.

Weiling Lin

[1] Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Zen Buddhism,” October 2002, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/zen/hd_zen.htm

[2] Jin-Shan Shen, Yu-Meng Xiao, and Chih-Long Lin, “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting,” Creative Education 15 (April, 2024): 652–77. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2024.154040

[3] Shen et. al., “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting.”

[4] Department of Asian Art, “Zen Buddhism.”

[5] Shen et. al., “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting.”

[6] Department of Asian Art, “Zen Buddhism.”

[7] Shen et. al., “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting.”

[8] Shen et. al., “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting.”

[9] Department of Asian Art, “Zen Buddhism.”

[10] Yukio Lippit, “Zenga: A Brief History,” The Gitter-Yelen Collection Online Catalogues, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, https://emuseum.mfah.org/catalogues/gitter-yelen-collection/menu/zenga-a-brief-history

[11] Shen et. al., “Exploring the Characteristics of Zen Painting.”