Calligraphy & Rubbing: The art of writing and transmitting the canon

Attributed to Mi Fu (Chinese, 1051-1107)

Calligraphy rubbing

Late 20th century

27 x 12 3/4 in.

Estate of Virginia A. Myers

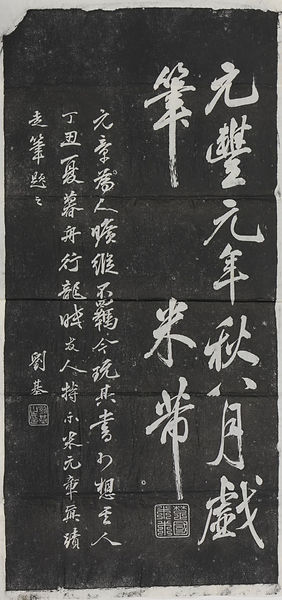

This piece attributed to Mi Fu is a rubbing of his calligraphic transcription of Tang Dynasty poet Cui Hao’s poem titled “Respectfully Harmonizing with Supervising Secretary Xu’s poem “Night duty”; offered to my friends.” Tang poetry was often selected for the content of calligraphic work to provide the viewer with literary and historical intrigue as well as aesthetic appeal of the brushwork itself.[1] The larger text on the right side is the last page of the work with the date and Mi Fu’s signature and seal. The smaller text on the left side is an inscription signed by Liu Ji (1311–1375) containing a commentary on the calligraphic work.

Mi Fu was well known not only for his skillful calligraphy, but also for his status as a connoisseur. Mi Fu started his career when he was young, by copying famous works of calligraphy that were originally produced by old masters.[2] Copying and learning through rubbing was a key practice in the calligraphic tradition in China due to the scarcity of original writings by ancient calligraphy masters.

This rubbing is an example of Mi Fu’s running script, or semi-cursive script, which is an informal script that is based on standard script Chinese and can come very close to cursive writing. The majority of Mi Fu’s work that transcribes poetry, lyrics, or prose, is written in running script. Running script originates from poetry and prose handscrolls written in the post-mid-Tang period.[3] Mi Fu modeled his fluid calligraphy style after Tang masters whose work included lots of twists and turns.[4] Although Mi Fu began his career by copying other masters, as he progressed, he was able to create his own distinct style of calligraphy.[5] Mi Fu’s running script is thick and full, with a tendency to extend both vertical and diagonal lines. This results in characters that occupy lots of space, in contrast to Liu Ji’s running script on the left, which is smaller and self-contained.The inscription on this rubbing bears a signature by Liu Ji, who was the chief advisor of the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty. Liu Ji was known as a prominent Daoist military strategist with strong intellectual abilities.[6] The notable identity of the inscription writer is important because it adds validity and credibility to the main body of work.

Lila Eggerling-Boeck

[1] Ronald Egan, “The Relationship of Calligraphy and Painting to Literature,” in The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature, ed. Wiebke Denecke, Wai-Yee Li, and Xiaofei Tian (Oxford University Press, 2017), 104-105.

[2] Nakata Yujiro, “Calligraphic Style and Poetry Handscrolls: On Mi Fu’s Sailing on the Wu River,” in Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy and Painting, ed. Alfreda Murck and Wen C. Fong (The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1991), 96.[3] Yujiro, “ Calligraphic Style and Poetry Handscrolls,” 99.

[4] Peter C. Sturman, Mi Fu: Style and the Art of Calligraphy in Northern Song China (Yale University Press, 1997), 63.

[5] Sturman, Mi Fu, 54-63.

[6] Hok-Lam Chan, “The Making of a Myth: Liu Ji’s Fictionalization in the Yinglie zhuan and Its Sequel,” in The Scholar’s Mind: Essays in Honor of Fredrick W. Mote, ed. Perry Link (The Chinese University Press, 2009), 51.

Ramon Lim (Chinese American, born in the Philippines, 1933)

Overnight in a Mountain Temple

2007

46 1/2 x 22 in.

Gift of the artist

2023.38

Ramon Lim (Chinese American, born in the Philippines, 1933)

Farewell to a Friend

2010

37 x 19 in.

Gift of the artist

2023.40

Ramon Lim (Chinese American, born in the Philippines, 1933)

Great Squares Show No Corners

2018

36 x 16 in.

Gift of the artist

2023.42

This group of scrolls represent the cursive calligraphy works by Dr. Ramon Lim (born 1933), a Chinese American artist based in Iowa City. Trained as a doctor and neurologist, Lim is Professor Emeritus at the University of Iowa and a calligrapher, painter, and writer. Born and raised in the Philippines, Lim started creating abstract paintings when he was in medical school in Manila. In later years, Lim turned his artistic interest to Chinese calligraphy in which he combines traditional practices and modern aesthetics.[1] Like all the Chinese calligraphers who came before him, Ramon Lim learned calligraphy by copying masterpieces from the past with the goal of developing his own artistic interpretation.

Lim specializes in cursive calligraphy, a script that developed around the end of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) and matured during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Initially developed as an abbreviated and quicker way of writing, cursive script simplifies the Chinese characters and turns multiple strokes into a continuous movement of the brush.[2] As an abstract painter, Lim was attracted to the expressive and rhythmic visual qualities of this form of writing. His cursive calligraphy draws inspiration from both ancient and modern masters from China. Lim cites Huaisu (737-799), a master of “wild cursive” calligraphy, as his main source of inspiration.

The scrolls on display in this exhibition all transcribe well-known texts from ancient China. 2023.38 presents “Overnight in a Mountain Temple,” a poem by Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai (or Li Bo, 704-762). Working with a non-conventional brush, Lim uses the split ends and low absorbency of chicken feather to create dramatic effects of “flying white.”

2023.40 features “Farewell to a Friend,” a poem by Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei (701-761). This piece shows stylistic affinity to modern calligraphy master Yu Youren (1879-1964). Yu is known for developing the so-called “standard cursive” that aims to make cursive calligraphy more accessible. Lim’s work captures a hallmark of Yu’s cursive calligraphy in that every character is separate from each other.

2023.42 is Lim’s interpretation of a single phrase from the Daode jing, an ancient Chinese classic that dates to the fourth or third century BCE and traditionally credited to Laozi. Here Lim creates a bold image with the characters’ simple forms and the vibrating lines inspired by the style of modern calligraphy master Lin Sanzhi (1898-1989).

Amy S. Huang

[1] Ramon Lim, An anthology of literary and artistic works of Ramon Lim (Manila: Philippine Chinese Literary Arts Association, 2008).

[2] National Museum of Asian Art, “Cursive script,” https://asia-archive.si.edu/learn/chinas-calligraphic-arts/cursive-script/

The Art of Transmission: Rubbing and Copying Traditions in Chinese Calligraphy

Throughout Chinese art history, few practices have been as crucial to cultural preservation and artistic development as the traditions of rubbing and copying calligraphy. These methods, refined over centuries, served not only to preserve important works but also to establish artistic lineages and maintain cultural continuity across generations. The intricate relationship between original works, their copies, and the subsequent interpretations of both reveals complex attitudes toward authenticity, preservation, and artistic innovation that differ markedly from Western traditions of art making and collecting.

The transmission and preservation of Chinese calligraphy through rubbing and copying represents a complex cultural practice that fundamentally shaped the development of this art form. As Amy McNair's seminal research demonstrates, these practices were not merely mechanical reproduction methods but rather sophisticated systems of cultural preservation that influenced both the "physical life" and "critical life" of calligraphic works.[1] Since the Later Han dynasty (25-220), ink-written calligraphy has been seen as an expression of the writer's personality, making the transmission of these works particularly significant.[2] The rubbing of running script attributed to Mi Fu in this exhibition, featuring his 1085 calligraphy of Cui Hao's poem with Liu Ji's 1337 inscription, exemplifies these traditions' enduring significance.

Historical Development and Technical Process

The practice of creating stone engravings and subsequent rubbings emerged as early as the fourth century BCE but gained particular prominence during the Tang and Song dynasties. Beginning in the tenth century, famous works of calligraphy in palace and private collections were systematically copied and engraved in stone.[3] The model-letters tradition (tiepai) formalized this practice through imperial compendia such as the Chunhua ge tie (992) and Daguan tie (1109). These collections served to canonize certain works and styles while establishing a systematic approach to transmission.[4]

Authentication and Connoisseurship

The question of authenticity in Chinese calligraphy presents fascinating complexities. McNair's discussion of Song dynasty connoisseurs Mi Fu (1052-1107) and Huang Bosi (1079-1118) reveals sophisticated debates about authenticity that went far beyond simple questions of originality. Their critical evaluations of the Chunhua ge tie, where they questioned nearly half of its attributions, demonstrates the complex relationship between original works and their reproductions.[5] Mi Fu, whose Running Script rubbing we examine, was himself a prominent critic of authentication practices, declaring in 1088 that he had "roughly divided [the letters] into genuine and fake."[6]

Social and Political Dimensions

The production of rubbings and copies served important social and political functions. McNair notes that the Song critics' reception of Northern Wei Buddhist inscriptions was heavily influenced by considerations of social class and cultural identity. Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072), a prominent Song dynasty scholar-official, expressed concern about the "vulgarity" of Northern Dynasty stele engravings, particularly their poor grammar and incorrect characters, which he attributed to their "barbarian" origins.[7]

Material Culture and Preservation

The physical aspects of rubbing and copying played a crucial role in preservation. McNair describes how the Chunhua ge tie deteriorated within a hundred years, demonstrating the vulnerability of even imperial collections.[8] The durability of stone engravings and the ability to produce multiple rubbings provided a more reliable means of preservation, as evidenced by the survival of Mi Fu's Running Script through late 20th-century rubbings.

Contemporary Significance

By the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), attitudes toward stele inscriptions had shifted dramatically. Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and other late Qing scholars began to appreciate anonymous Northern Dynasty inscriptions for their aesthetic qualities rather than their historical or social significance.[9] This shift in critical reception demonstrates how the evaluation of calligraphic works could evolve over time, independent of their original context or authorship.

The late 20th-century rubbing of Mi Fu's Running Script exemplifies the enduring relevance of traditional reproduction practices. While modern technologies offer new means of reproduction, the rubbing technique maintains a direct physical connection to historical works that many practitioners and collectors continue to value. The presence of Liu Ji's 1337 inscription adds another layer of historical significance, demonstrating how these works accumulated meaning through generations of engagement and interpretation.

Conclusion

The practices of rubbing and copying in Chinese calligraphy represent a sophisticated system of cultural transmission that shaped the art form's development over centuries. Through examples like Mi Fu's Running Script rubbing, we can understand how these practices served multiple functions: preservation of important works, transmission of artistic techniques, establishment of cultural authority, and creation of new artistic possibilities through reinterpretation. McNair's research reveals not just technical processes but fundamental aspects of Chinese cultural attitudes toward artistic creation, preservation, and transmission.[10]

Madison Bockenstedt

[1] Amy McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China: Recension and Reception," The Art Bulletin 77, no. 1 (March 1995): 106.

[2] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 106.

[3] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 106-7.

[4] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 107-8.

[5] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 107-8.

[6] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 107.

[7] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 110-11.

[8] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 107.

[9] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 113-14.

[10] McNair, "Engraved Calligraphy in China,” 113-14.